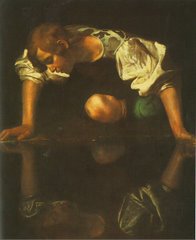

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, "The Land of Cuckcaigne", 1567

The alchemy of critical perception

We feel that a lack of training in “critical perception” is an issue that Western culture should address as soon as possible in order to nurture in our citizens the development and refinement of the natural capacity of the mind to perceive and locate information in contexts and in sets.

Throughout the 20th century, modern mass media performed the tasks of facilitating, inhibiting or stimulating the critical perception of the masses, conveying in a subtle, subliminal manner an approval or disapproval of proposed solutions whenever it was felt that, for the common good, widespread acceptance or rejection of certain political, ethical or cultural ideas would be required.

“We would do well to teach children, from primary school onwards, that all perception is a reconstruction of reality elaborated by the brain and determined by our sensory organs, and that no knowledge can be acquired without “interpretation”.”

Anyone who writes and offers comments on any aspect of reality through any available means of communication interprets facts on the basis of his or her own particular vision of the world.

The ability to enhance one’s powers of critical perception does not normally depend on one’s education or cultural background, a high professional or economical status or any particular philosophical, political or religious stance.

All through life, people express their inner evolution in terms of self-awareness and their powers of discrimination and mental comprehension of reality; and this is reflected in particular moods, feelings, a certain philosophy or an historical awareness. Understanding that perception is modelled as a “backdrop of consciousness” is extremely useful and leaves us free to evaluate, with a reasonable degree of detachment, the theorems, theses and hypotheses that derive from various different points of view and upon which are erected the foundations of all hegemonic frameworks of knowledge.

“Thus, starting with contradictory appraisals of a single event - for example, a car accident - we can illustrate the possibility of the occurrence of perceptions that often result in forms of even hallucinatory rationalisation.

It is possible to describe cases of imperfect perception caused by the force of habit or poor attention, and other cases where we might encounter a lack of attention towards certain insignificant details, hurried interpretations of unusual details and, above all, a poor capacity to capture images or stimuli as a whole or an absence of reflection.” [i]

The fundamental difference between a good perception of a series of elements and a very poor perception of reality, which is often reductive and uncertain, is due to the difficulty in maintaining one’s attention for a sufficiently long period of time until the “bits” of information one perceives can complete their “circular course” and are deposited in the memory (after the stimulus has caused an effect within the three different systems: i.e., cognitive-perceptive, attentional and emotional.

Attention is most definitely a capacity that can be improved by study and application, daily mental exercise and the habit of reflecting on content (not only sensorial, or that which is acquired by the immediate satisfaction of curiosity) but it can also be enhanced by information often invisible to the physical eye.

Brueghel metaphorically describes the preliminary phases of perception: those which allow the soul (symbolised in the form of a woman) to leave the dark tunnel of unawareness to observe (comfortably resting on a velvet cushion) the actors and protagonists of history and life. A woman, wearing a helmet with an open visor and protected by a breast-plate and iron gloves, looks out upon life. She is as determined as a warrior “compelled” to witness cruelty, human misery and the illusions that fill the chronicles of daily life.

To observe reality directly, without prior interference with the powers of subjective judgement (often interpreted as conformist prejudice or as an unconscious refusal to elaborate differences, emotional anxiety, or moral inhibition engendered by taboos), requires a serene, trusting acceptance of all “light frequencies” and an acceptance of the whole spectrum of experiences during our earthly existence.

If we ignore or pretend to ignore the existence of evil, cruelty and violence or moral, ethical and ecological sin, then we remain blind, stupid and emarginated from true reality and the knowledge of truth for our entire life. Ignoring or pretending to ignore that errors of evaluation due to an excess of rationalisation or pragmatism (albeit with the apparent aim of pursuing collective benefits) can lead to disasters, destruction and the end of every hope of reconciling conflicts implies the mere illusion of being in the right or of having full control.

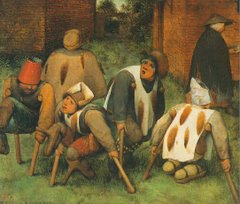

Brueghel was the first Renaissance artist to denounce the ills of society, as he saw them in the 1500s, and he does so with the detached lucidity of an observant journalist or pitiless critic, with no form of compassion or historical or moral justification. What guides his imagination is a certain curiosity that rapidly evolves into critical perception, discriminating reason and ethical conscience.

It is fascinating to note that Brueghel reaped the rewards of his research and lucidity only one year after he had produced “The Land of Cuckaigne”. The artist’s powers of perception seem to be increasingly enhanced when he depicts the worlds of “the blind” and the “crippled”. In these highly effective paintings we also find two extraordinary allegories of a “sick society” incapable of just action and incapable of understanding reality. Brueghel’s society is one in which the leaders of our world and the representatives of the collective consciousness are utterly blind and incapable of identifying changes that will address the real needs of humanity.

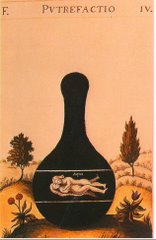

The three paintings we refer to reveal a common denominator in their composition and, it would appear, a sole source of inspiration. It is well known that the esoteric artist Brueghel was also a mystic with a profound interest in alchemy. He was evidently well-acquainted with the symbols and lore of the astrologers and alchemists and clearly perceived the occult meanings of parables contained in the Gospels.

The “actors” in the scenes are portrayed in a theatrical world that recites its own folly and unleashed libido and reveals a sacredness which no-one deeply believes in.

Breugel’s vision however is neither moral, nor ethical. He appears not to take sides and chooses - or perhaps, despite himself, is rather obliged - to assume the position of a “witness”: the position of an individual who cannot avoid observing reality with critical awareness.

In Italy, and probably in Florence and Rome, he assimilated the basic principles of an alchemical vision of the material and spiritual worlds.

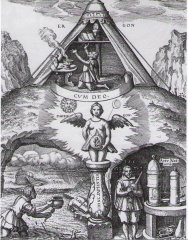

Alchemical knowledge can be structured into four parts, which can be seen as corresponding with the four arms of the Christian cross. Alchemy is fundamentally a process in which psychic energy evolves along the “horizontal plane” of time to activate rationality, intuition and trans-logical consciousness, which develop on the “vertical plane”, rising from the depths of the soul to the mind, which Augustine of Hippo saw as an imago Dei.

When the vertical axis, generated by the evolving “psychic” soul, intersects the horizontal line (symbolising the spatial orientation of critical perception which expands through philosophical, psychological or artistic activity), a progressive “distillation” of the philosopher’s mercury occurs. This metaphor refers to the transmutation of the intelligence of the soul into the rational mind.

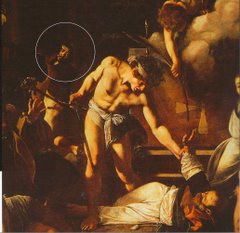

By attaining critical perception (the raised visor of the helmet), the egocentric motivations, intentions and sentiments present in individuals are revealed to the mind, and one may appreciate how such weaknesses result in an individual becoming the victim of another’s libido (the dead soldier with an amputated arm) or, inversely, the victim of one’s own materialistic libido (the peasant depicted in the lower frame lies exhausted on the ground, overcome by fatigue and hard labour) or the victim of a desire to escape reality by means of the imagination, fantasies and the search for sensual gratification (the opulent waster).

In “The Land of Cuckaigne”, the first three frames created by the cross represent the three processes of transmutation of common intelligence into a critical, historical and psychological awareness of social dynamics, individual and collective libido and the unconscious and conscious mechanisms of avoidance of personal responsibility, which will inevitably lead to destruction, greed and ignorance.

In the painting, we see that food is within arm’s reach on the tree of knowledge, on a plane just a little higher than sensorial awareness, but none of the three subjects depicted is capable of attaining this level.

In the upper right quarter, we notice a man trying to find his way through the clouds. Here, the metaphor warns us of the dangers of induced illusion, self-illusion and erroneous perception, and, eagerly leaning forward, the subject is descending to the land of cockaigne, where food, money and riches are there for the taking and plucked geese are offered to him on a silver platter.

Brueghel’s allegory is thus composed of four metaphors which fully describe the evolution completed by the individual who decides to observe reality from “the point where the sun rises”, from the point where the clear sight of critical reason can observe the bloodshed, violence and wars generated by human folly, which in turn is a result of egocentric libido, considered by the Renaissance alchemists as the real original sin to be eradicated from the bio-psychological nature of mankind.

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento