THOMAS’S DOUBT

FROM RATIONAL CURIOSITY

TO CRITICAL COMPREHENSION

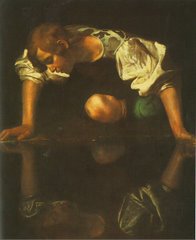

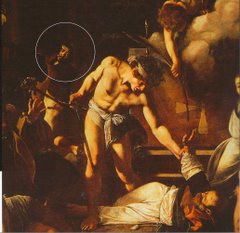

The Incredulity of St Thomas not only presents us with the four faces of Reason. In this work, Caravaggio emblematically represents the saint’s rational curiosity through his expression and extended index finger in an event, and technique, capable of undermining faith, opinion and empirical practice.

“Above all, and as a link between knowledge and power, the will requires technique in order to express and differentiate itself from dreams or mere desire without realisation.”

Caravaggio’s creativity is revealed in a desire to know the truth through a “technical” action. For an artist, a “technical” action is a process whereby a subject is “elaborated” within a geometrical grid capable of structuring and inspiring a second level of comprehension. The symbolic construction elevates the artist’s work from the level of a simple exercise to an authentic application of preordained knowledge according to a scheme which already exists in the creative mind and which remains hidden to those who operate in the domain of “thought as a technique of domination”.

“As far as I am concerned, any activity incapable of rationally explaining the nature of its object or its instruments or is incapable of explaining facts or linking them to a cause is not a technique but a mere exercise or practice.”

In art and painting, the arrangement of objects and content according to the lines of the alchemical cross is no novelty. For example, diagonal lines may be used to generate a sense of tension and a breaking up of schemes. Such configurations can be adopted to introduce symbolic elements required to establish a meaningful link with the theme of the composition.

A double diagonal establishes a relationship between the parts of an arrangement that must subtly intercommunicate through operations of a sensorial (red line) or conceptual type (blue line).

The red line created by Caravaggio aligns the left eye and nose of the two apostles with Jesus’ middle finger (faith). The blue line is the direction from which the light of comprehension gradually illuminates the scene and draws attention to the critical faculty in Thomas’s sense smell, the lips of Jesus, and, in the shadier part, the index finger of the left hand (a symbol of the psychic component upon which all forms of curiosity tend to feed). The geometrical layout of the composition is an artifice used to rationally “control the scene”, the dynamics of the gestures of the figures portrayed and the subtle transmission of the content of the painting to the observer.

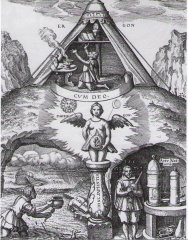

The six sections of the circle, used by Botticelli in his Madonna of the Pomegranate (Virgin Mary with Child and six Angels), form a technique used to instil and “compress” in a symbolic form large quantities of information and alchemical knowledge in an “emblem”. The “Word” itself is thus “incarnated” in visual iconic material and becomes increasingly complex as the conceptual plane shifts from perceived themes to principles of knowledge and on to individual consciousness and the universal spirit. Rationality sets up an effective barrier against error and illusion, however we should leave our minds open to the language of symbols. In this way, rational criticism can remain “open” to stimuli which can challenge its schemes. Otherwise, it would become restricted by doctrine and mere rationalisation; we would witness an enforced “squaring of the psychic circle” and an a priori refusal to forgo the power of the “Word” to inspire, teach, nourish and encourage the rational mind to trust in the cognitive potential of the creative soul.

Caravaggio’s work leads us into a dimension quite different from that perceived in Botticelli’s paintings.

Botticelli is interested in codifying the three stages of development which the soul must pass through in order to evolve from the level of psychic and emotional sensibility to self-knowledge and knowledge of the world through the experience of sentiments which have the effect of modelling logical and rational consciousness.

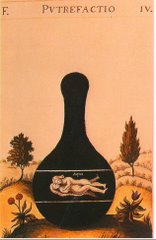

Caravaggio on the other hand aims at investigating the critical stage that occurs during the “death and transformation” of the psychic soul in the creative mind: a process in which we encounter the emergence of the phenomena of sensorial perception and the results of intuitive knowledge. Within the space of just a few years, Caravaggio rapidly evolved in the critical perception of reality and captured the eternal conflict between the natural naivety of the soul and an egocentric libido which manifests in the form of craftiness, deception and psychic manipulation.

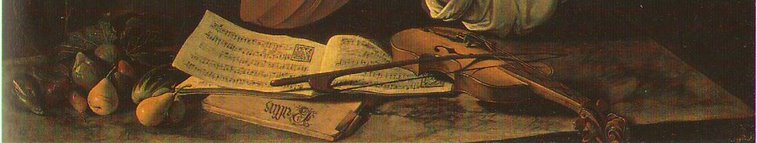

After The Cheats (1494) and The Fortune-Teller (1595), with his painting The Concert (1595), Caravaggio concludes his psychological analysis of human conflicts and comprehended the developmental relationships between intuition and sensation, and between thought and sentiment, the four “corners” of the alchemical cross, from which emerge every degree of perception and all forms of knowledge.

If Botticelli’s work is of a purely “theoretical” nature, in The Concert Caravaggio interprets the “operative evolution” from the stage of logical, deductive and inductive rationality to the stage of creative discrimination reflected in the The Lute Player, who is free to decide which musical score should be played. In the same way, Caravaggio begins to present an a priori selection of subjects to be studied, and places them in a specific light, providing metaphors that reflect a critical and intuitive reason capable of probing sentiment, revealing passions, and inspiring various levels of interpretation.

Like St. Thomas, Caravaggio believes solely in evidence which emerges from empirical studies of reality. The “incarnate mind” is not only the fruit of action, trials or conflicts generated by human relations and relationships with power or through a comparison – occasionally violent and irrational - with the environment.

The cognitive experience of Caravaggio reveals itself through an emotional awareness and a knowledge that emanates from critical reason. However, above all, it is experienced in the realistic perception of human nature, its psychological weaknesses and limits (especially mental), as can be seen in the artist’s highlighting of the numeral III beside the number 8: the symbol of the capacity to abandon subjective convictions.

A “symmetry” of analyses and points of view emerge from life experiences assimilated in the memory and from virtual experience produced through creative imagination; and in these analyses and points of view we can detect the “double process” that stems from constructive rationality and the intuitive mind.

Goliath – a figure with whom the painter can be identified - is decapitated three times, and, by such an action, Caravaggio succeeds in eliminating the biological, social and cultural causes of errors of reason: errors that emerge from the ego’s identification with the behaviour, ideologies, doctrines, philosophies and principles that originate in the process of rationalisation of human, individual or collective resources.

The rational technique of “assembling” experiences in order to obtain a specific model of knowledge carries with it a possibility of error and illusion when it becomes perverted rationalisation.

“We see rationalisation as “rational” as it constitutes a perfectly logical system grounded in deduction or induction, however it is founded on mutilated or false bases and opposes any falsification process or empirical verification made possible by examination of the elements considered.

Rationalisation is a “closed” process, while rationality is “open”. Rationalisation accesses the same sources as rationality but constitutes one of the most important sources of error and illusion. Thus, a doctrine based on a mechanical and deterministic model of the world is not rational but a form of rationalisation.”[1]

Caravaggio perceives this danger in the biblical story of Abraham, who is commanded by the god of limitation and obligation (Saturn) to sacrifice his son Isaac (a metaphor reflecting a creative impulse in the form of an act of obedience and the observation of rules or principles). Again, in the Sacrifice of Isaac, Caravaggio reinterprets the sacrificial gesture in the light of good sense, logic, critical reason and solar rationality, in which we find a reflection of Greek philosophy and the technical praxis of all sciences based on a profound knowledge of human nature.

The angel arrives from heaven just in time to stop the knife (a symbol of absolute, univocal rationalisation, which often tends to cut away, sever and simplify) and from the opposite direction appears the head of a goat (indicated by the angel’s index finger). This is the symbol of a form of rationality which is “open”, domesticated, productive and willing to accept debate and share experiences: a quality typical of the individual that observes and accepts the biological order in which the alchemist recognises a divine presence.

[1] e.Morin, I sette saperi necessari per il tempo futuro

FROM RATIONAL CURIOSITY

TO CRITICAL COMPREHENSION

The Incredulity of St Thomas not only presents us with the four faces of Reason. In this work, Caravaggio emblematically represents the saint’s rational curiosity through his expression and extended index finger in an event, and technique, capable of undermining faith, opinion and empirical practice.

“Above all, and as a link between knowledge and power, the will requires technique in order to express and differentiate itself from dreams or mere desire without realisation.”

Caravaggio’s creativity is revealed in a desire to know the truth through a “technical” action. For an artist, a “technical” action is a process whereby a subject is “elaborated” within a geometrical grid capable of structuring and inspiring a second level of comprehension. The symbolic construction elevates the artist’s work from the level of a simple exercise to an authentic application of preordained knowledge according to a scheme which already exists in the creative mind and which remains hidden to those who operate in the domain of “thought as a technique of domination”.

“As far as I am concerned, any activity incapable of rationally explaining the nature of its object or its instruments or is incapable of explaining facts or linking them to a cause is not a technique but a mere exercise or practice.”

In art and painting, the arrangement of objects and content according to the lines of the alchemical cross is no novelty. For example, diagonal lines may be used to generate a sense of tension and a breaking up of schemes. Such configurations can be adopted to introduce symbolic elements required to establish a meaningful link with the theme of the composition.

A double diagonal establishes a relationship between the parts of an arrangement that must subtly intercommunicate through operations of a sensorial (red line) or conceptual type (blue line).

The red line created by Caravaggio aligns the left eye and nose of the two apostles with Jesus’ middle finger (faith). The blue line is the direction from which the light of comprehension gradually illuminates the scene and draws attention to the critical faculty in Thomas’s sense smell, the lips of Jesus, and, in the shadier part, the index finger of the left hand (a symbol of the psychic component upon which all forms of curiosity tend to feed). The geometrical layout of the composition is an artifice used to rationally “control the scene”, the dynamics of the gestures of the figures portrayed and the subtle transmission of the content of the painting to the observer.

The six sections of the circle, used by Botticelli in his Madonna of the Pomegranate (Virgin Mary with Child and six Angels), form a technique used to instil and “compress” in a symbolic form large quantities of information and alchemical knowledge in an “emblem”. The “Word” itself is thus “incarnated” in visual iconic material and becomes increasingly complex as the conceptual plane shifts from perceived themes to principles of knowledge and on to individual consciousness and the universal spirit. Rationality sets up an effective barrier against error and illusion, however we should leave our minds open to the language of symbols. In this way, rational criticism can remain “open” to stimuli which can challenge its schemes. Otherwise, it would become restricted by doctrine and mere rationalisation; we would witness an enforced “squaring of the psychic circle” and an a priori refusal to forgo the power of the “Word” to inspire, teach, nourish and encourage the rational mind to trust in the cognitive potential of the creative soul.

Caravaggio’s work leads us into a dimension quite different from that perceived in Botticelli’s paintings.

Botticelli is interested in codifying the three stages of development which the soul must pass through in order to evolve from the level of psychic and emotional sensibility to self-knowledge and knowledge of the world through the experience of sentiments which have the effect of modelling logical and rational consciousness.

Caravaggio on the other hand aims at investigating the critical stage that occurs during the “death and transformation” of the psychic soul in the creative mind: a process in which we encounter the emergence of the phenomena of sensorial perception and the results of intuitive knowledge. Within the space of just a few years, Caravaggio rapidly evolved in the critical perception of reality and captured the eternal conflict between the natural naivety of the soul and an egocentric libido which manifests in the form of craftiness, deception and psychic manipulation.

After The Cheats (1494) and The Fortune-Teller (1595), with his painting The Concert (1595), Caravaggio concludes his psychological analysis of human conflicts and comprehended the developmental relationships between intuition and sensation, and between thought and sentiment, the four “corners” of the alchemical cross, from which emerge every degree of perception and all forms of knowledge.

If Botticelli’s work is of a purely “theoretical” nature, in The Concert Caravaggio interprets the “operative evolution” from the stage of logical, deductive and inductive rationality to the stage of creative discrimination reflected in the The Lute Player, who is free to decide which musical score should be played. In the same way, Caravaggio begins to present an a priori selection of subjects to be studied, and places them in a specific light, providing metaphors that reflect a critical and intuitive reason capable of probing sentiment, revealing passions, and inspiring various levels of interpretation.

Like St. Thomas, Caravaggio believes solely in evidence which emerges from empirical studies of reality. The “incarnate mind” is not only the fruit of action, trials or conflicts generated by human relations and relationships with power or through a comparison – occasionally violent and irrational - with the environment.

The cognitive experience of Caravaggio reveals itself through an emotional awareness and a knowledge that emanates from critical reason. However, above all, it is experienced in the realistic perception of human nature, its psychological weaknesses and limits (especially mental), as can be seen in the artist’s highlighting of the numeral III beside the number 8: the symbol of the capacity to abandon subjective convictions.

A “symmetry” of analyses and points of view emerge from life experiences assimilated in the memory and from virtual experience produced through creative imagination; and in these analyses and points of view we can detect the “double process” that stems from constructive rationality and the intuitive mind.

Goliath – a figure with whom the painter can be identified - is decapitated three times, and, by such an action, Caravaggio succeeds in eliminating the biological, social and cultural causes of errors of reason: errors that emerge from the ego’s identification with the behaviour, ideologies, doctrines, philosophies and principles that originate in the process of rationalisation of human, individual or collective resources.

The rational technique of “assembling” experiences in order to obtain a specific model of knowledge carries with it a possibility of error and illusion when it becomes perverted rationalisation.

“We see rationalisation as “rational” as it constitutes a perfectly logical system grounded in deduction or induction, however it is founded on mutilated or false bases and opposes any falsification process or empirical verification made possible by examination of the elements considered.

Rationalisation is a “closed” process, while rationality is “open”. Rationalisation accesses the same sources as rationality but constitutes one of the most important sources of error and illusion. Thus, a doctrine based on a mechanical and deterministic model of the world is not rational but a form of rationalisation.”[1]

Caravaggio perceives this danger in the biblical story of Abraham, who is commanded by the god of limitation and obligation (Saturn) to sacrifice his son Isaac (a metaphor reflecting a creative impulse in the form of an act of obedience and the observation of rules or principles). Again, in the Sacrifice of Isaac, Caravaggio reinterprets the sacrificial gesture in the light of good sense, logic, critical reason and solar rationality, in which we find a reflection of Greek philosophy and the technical praxis of all sciences based on a profound knowledge of human nature.

The angel arrives from heaven just in time to stop the knife (a symbol of absolute, univocal rationalisation, which often tends to cut away, sever and simplify) and from the opposite direction appears the head of a goat (indicated by the angel’s index finger). This is the symbol of a form of rationality which is “open”, domesticated, productive and willing to accept debate and share experiences: a quality typical of the individual that observes and accepts the biological order in which the alchemist recognises a divine presence.

[1] e.Morin, I sette saperi necessari per il tempo futuro

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento